In 1922, when only one in 10 Americans owned a car, GM launched an undercover campaign to destroy the then-dominant public transportation system. The campaign, which took 30 years to fully implement, focused on the country's clean (powered by electricity) and safe (accidents were infrequent) streetcar system.

GM, in partnership with Standard Oil of California and Firestone, began by buying the largest busmaker in the U.S. It then secretly funded a company called National City Lines, which by 1946 controlled streetcar operations in 80 cities.

Despite public opinion polls that, in Los Angeles for instance, showed 88 percent of the public favoring expansion of the rail lines after World War II, NCL systematically closed its streetcar systems down until, by 1955, only a few remained.

A federal antitrust investigation resulted in both indictment and conspiracy convictions for GM executives, but destroying a public transportation network that would cost hundreds of billions of dollars to reproduce today cost the company only $5,000 in fines.

Talk about a slap on the wrist! I've always thought it was a pretty incredible story and have always received similar responses with those I've shared it with. I just happened to bring it up again this morning with my wife. She surprised me with a mysterious reply: "You know, there's another chapter to that story you haven't told yet!" So with her inspiration and a little research into a company she mentioned named Alweg, I came across this fascinating follow-up:

LA's Worst Transit Decision

another Monorail Society Exclusive!

by Kim Pedersen

Fanciful art rendering of proposed LA monorail station, circa 1963.

In 1963, Los Angeles politicians were given an offer too good to refuse. The Alweg Monorail Company, which had gained world-wide recognition for its demonstration monorail at the 1962 Seattle Century 21 Exposition, was looking to establish a major foothold in the world of urban rail transit. "We are pleased to submit this day a proposal to finance and construct an Alweg Monorail rapid transit system 43 miles in length, serving the San Fernando Valley, the Wilshire corridor, the San Bernardino corridor and downtown Los Angeles." So wrote Sixten Holmquist, then President of the Alweg Rapid Transit Systems in his June 4, 1963 letter to the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). He went on to detail the financing aspect, "this is a turn-key proposal in which a group will share risk, finance the construction, and turn over to MTA a completed and operating system to be repaid from MTA revenues." The entire system came to $105,275,000, "plus any applicable sales tax." Alweg also agreed to conduct feasibility studies for expansion of the system over the entire Los Angeles Metropolitan area if the offer was accepted. Undoubtedly, if the monorail had been built, it would by now have been expanded to all major LA destination points and beyond.

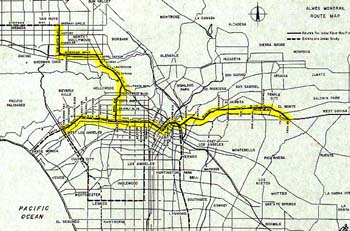

Outline of 1963 Alweg proposal for Los Angeles, California.Most people in Los Angeles today are totally unaware of Alweg's offer. The subway system that today parallels only a tiny portion of what would have been the LA Monorail alignment is an extraordinarily expensive joke. An unfortunate joke that has cost USA and California taxpayers billions of dollars, not millions, and yet it still doesn't travel far enough to be of any great value to most LA basin citizens.What happened to the Alweg proposal? In their infinite wisdom, Los Angeles supervisors at the time rejected the wonderful offer in favor of no rail. A former Alweg engineer once told me that there was much excitement for the proposal at the time, that is until Standard Oil got involved. Practically overnight support for the project disappeared amongst LA politicians. What could have been the start of monorail construction all across the USA was stopped cold before it even got started.

How about full-scale Alweg trains slipping in and out of LA buildings?Ray Bradbury, world-renowned science fiction writer and futurist, recently wrote in Westways Magazine about the terrible decision in an article on the future of LA. He wrote...

"on New Years Day 2001, let us pour 10,000 tons of cement into our never-should-have-been-started, never-to-be-finished subway, for final rites. Its concept was always insane, its possible fares preposterous. Even if it were finished and opened, no one could afford to use it. So kill the subway and telephone Alweg Monorail to accept their offer, made 30 years ago, to erect 12 crosstown monorails--free, gratis--if we let them run the traffic. I was there the afternoon our supervisors rejected that splendid offer, and I was thrown out of the meeting for making impolite noises. Remember, subways are for cold climes, snow and sleet in dead-winter London, Moscow or Toronto. Monorails are for high, free, open-air spirits, for our always-fair weather. Subways are Forest Lawn extensions. Let's bury our dead MTA and get on with life."Well said Ray.

What a coincidence, Standard Oil again! I found it interesting that Ray Bradbury had participated and claimed to advocate his support for this project. Another blog focused on Walt Disney's fascination with the monorail provides further details:

Along with Walt, author Ray Bradbury was also a big fan of the monorail technology. Bradbury tried to encourage the City of Los Angeles to build a system. He formed a citizen’s group called Save Rapid Transit and Improve Metropolitan Environments. He had admired the multi-modal and successful transit system in San Francisco and thought a layered system like that would work in Los Angeles. He said, “Look, the psychology of the monorail is what makes it superior. First of all, it’s not elevated like the old trains in Chicago. It’s up in the air, but it doesn’t make noise…you hardly hear it.” Bradbury added, “The important thing is that it’s above the traffic, and would glide past the traffic.”

The Alweg Monorail Company agreed with Bradbury on the merits of the technology and proposed a demonstration system for the City of Los Angeles. After the success of the system at Disneyland and the experienced gained at the 1962 Seattle Century 21 Exposition, Alweg was looking for a way to expand the business. So, on June 4, 1963, President of the Alweg Rapid Transit Systems, Sixten Holmquist, approached the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) and made them an offer.

The press release said, “We are pleased to submit this day a proposal to finance and construct an Alweg Monorail rapid transit system 43 miles in length, serving the San Fernando Valley, the Wilshire corridor, the San Bernardino corridor and downtown Los Angeles.” The offer was for “a turn-key proposal in which a group will share risk, finance the construction, and turn over to MTA a completed and operating system to be repaid from MTA revenues.” The budget for the initial monorail network, including rolling stock, was estimated to be $187.5 million. Alweg would also conduct feasibility studies for expansion of the system to cover the entire Los Angeles region. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1965, Walt said, “A monorail would be a natural attraction to thousands of people who would just ride it because it is something new and different. And it is needed. It’s not something that would be scrapped after two years.” Another competitor proposed a 75 mile suspended car system at a cost of $182.3 million.

Both companies promised to build the systems for “free” in exchange for the next 40 years of passenger revenues to bond against. The offer meant that the Los Angeles region would have had the backbone of a revolutionary mass transit system for no cost to the taxpayers. Political pressure from the Standard Oil Company dampened the Board of Supervisors and the LAMTA enthusiasm for the project.

http://micechat.com/blogs/samland/1850-disneylands-alweg-monorail-walt-disneys-highway-sky.html

I feel very deprived that this possibility did not come to pass. The end result of this stonewalling by the industrial fossil fuel titans is that, to bring this back to James Howard Kunstler's insight, “We’re literally stuck up a cul-de-sac in a cement SUV without a fill-up”. For those of you who haven't seen The End Of Suburbia, you'll understand the full context of that quote when you watch it.

No comments:

Post a Comment